Head a few miles up the beach from downtown Galveston and you can see the future.

Galveston Island, like much of the Texas coast, is a spit of sand. Along its eastern flank runs hard-packed, broad beach more suited to strolling, cruiser-biking, and running than burying oneself. You can wade out a hundred yards and still stand waist deep.

The place where the family and I stayed last week was residential, a cluster of vacation homes five miles from the far reaches of the busy sections of the Seawall district and its hotels, restaurants, vape shops, and pedal-car rentals. Much of the neighborhood was built in the last 30-40 years. Many won’t make it that long again going forward.

The sea level rise that’s coming with climate change is tricky to predict, but even conservative models are guessing about a foot of added ocean will lap (and, sometimes, smash) against these Galveston Island sands by midcentury.

Midcentury is 29 years from now. For someone on the north side of 50, 2050 sounds like the jetpack future. But then I consider that 29 years ago was 1992. Seems like a long time ago, sure. But not that long ago.

The future one sees on Galveston Island (we stayed near Pirate’s Beach, for those familiar with the area) involves houses being chastened and ultimately defeated by the sea. This despite all the stilts. A few photos:

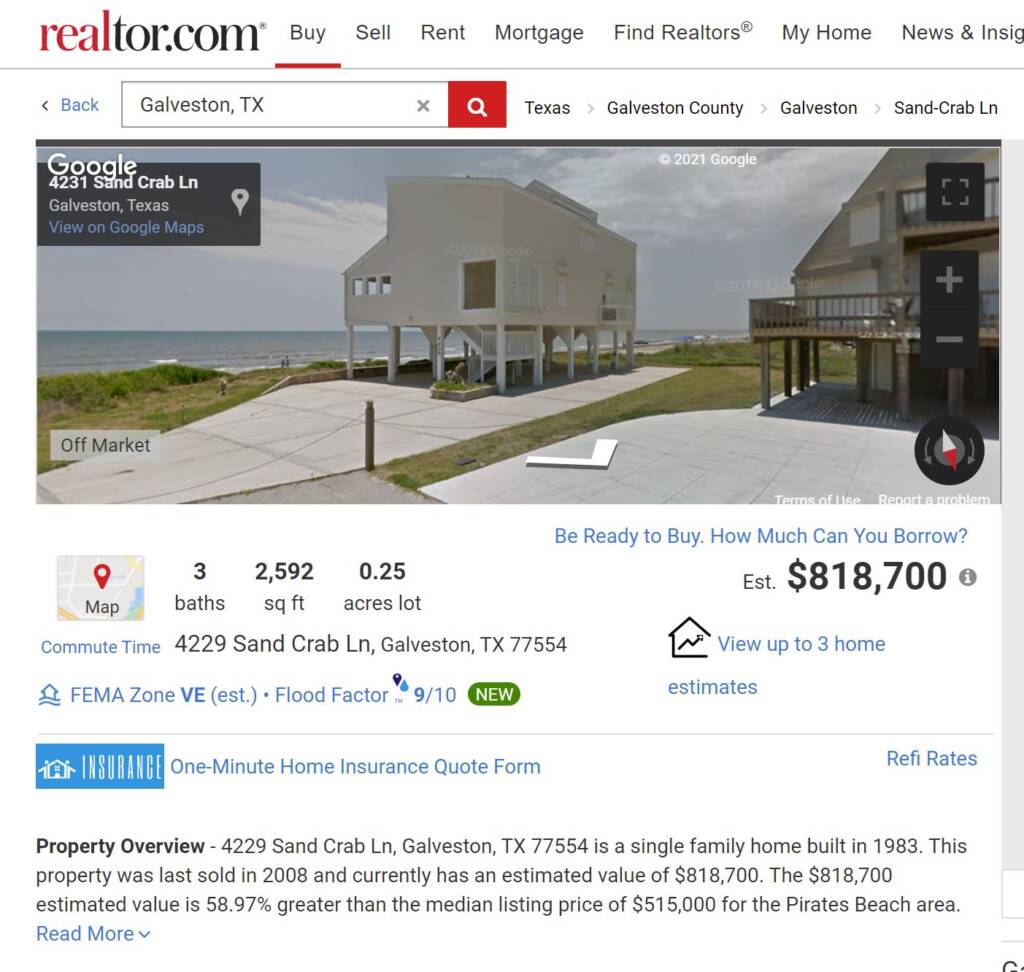

Here’s 4229 Sand Crab Lane (not sure why the Google Map shows it as 4231). It’s about three quarters of a mile up the beach from where we stayed. The homes in subsequent photos are all within a short walk of it. Looks nice, doesn’t it? Well…

Here’s what it looked like on March 30. Note the fraying sacks in the sand to the left. There are many more. Here’s a close-up:

I thought they were sandbags; actually, they had been form-filled with concrete — four-foot tonsil stones of untold tonnage shedding microplastics for the consumption of Gulf of Mexico wildlife. This particular house juts out toward the water a solid 40 yards beyond its neighbors. The synthetic boulders don’t seem to be doing much good. They looked a bit better in their heyday:

This is just what the sea does when you get in its way.

A bit down the beach is the yellow house visible above and in the lead art of this post:

I’d say, generously, that the sand at the point of the pillars is two feet above sea level mid-tide (tide was out here).

Most houses are in a better position. But the sea is quite obviously relentless:

Streets don’t typically cliff off quite like that, to my recollection.

Apparently the locals feel that strewing dead foliage about will totemically ward of the rising tides of global warming. Two more of several examples along that stretch:

And:

Yes, I know: the dried-out foliage will slow the sands’ departure. Just as an umbrella made of tissue paper will stop rain.

Briefly.

Other owners seem to be banking on berms:

But even berms have their issues, apparently:

Those are sprinklers and the piping that serves them poking out of the collapsed earth.

What’s strange to me is that interactive maps from the likes of NOAA and Climate Central show the homes along these beaches to be safe with even three or four feet of sea level rise – a reasonable guess for the end of the 21st century, though melting in Greenland and West Antarctica and God knows what else could prove the models blissfully optimistic.

Consider, though, the state of these houses in early 2021. And consider also that every inch of sea-level rise erodes away something like 100 inches of beach. A foot of sea level rise by midcentury, then, would shave 1,200 inches of beach – 100 feet or about 33 yards – of sand. Galveston’s beach is pretty wide, but 33 yards would erase most of it, even at its expansive low tide.

Consider also that these estimates use mean monthly high water (MMHW) projections. That is, no inundating storms, no hurricanes (which are both strengthening with warmer waters and moving slower with global warming), no storm surges. These things happen in places like Galveston. The below aerial photo was taken before Hurricane Ike came through in 2008. It looks right down Pelican Lane, the street our rental house was on, in fact.

Pelican Lane — temporarily the Pelican River — starts at the arrow. Not sure the berms and dead foliage did a whole lot of good.

Let’s face it: many of these Galveston Island homes are construction-industry versions of fast fashion: call it fast architecture. There’s a brand-new, lovely house right on the beach at the end of Pelican Lane. They built it in place of the one that’s on fire in the above photo. They scraped the one next to it on beach side. Now it’s a yard protected by — you guessed it —

A berm.

Pretty as an H&M dress, isn’t it?

It’s not far-fetched to believe that this fine structure’s utility will have gone threadbare within 30-40 years, and scraping and starting over again won’t be an option by then. Probably shouldn’t have been an option with this one, and probably wouldn’t have been if it hadn’t been for market-distorting subsidies courtesy of the National Flood Insurance Program.

It’s a lovely place, Galveston Island. But it doesn’t take a crystal ball to recognize that, to enjoy it while it lasts, you’re better off renting than buying.