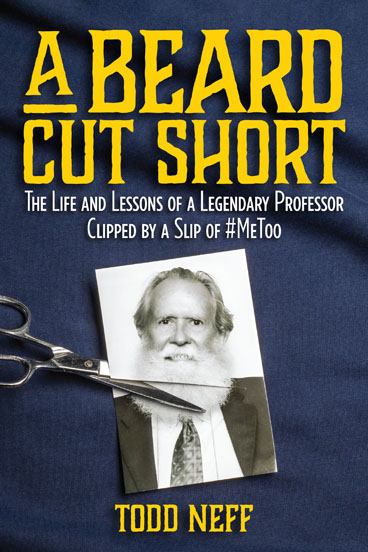

There are many stories in my new book, A Beard Cut Short. This one is about how it came to be.

Quick summary: a blog post led to a book.

The blog post is here. I wrote it shortly after I learned that John Rubadeau, a former teacher of mine at the University of Michigan, a mentor, and a longtime friend, was fired on the grounds of undisclosed sexual-harassment allegations.

Into that blog post, I pasted the contents of the email I had written to University of Michigan President Mark Schlissel. Mine was one of 128 written in support of our former teacher. I closed it with this:

I’m not familiar with the details, but I would assume, given his prominence and popularity, they will come to light. Will they wilt in the sunshine?

Little did I know I would be spending hundreds of hours providing that sunshine. And yes, the details wilt.

John was an English Department lecturer who taught writing – “The Art of the Essay” and “Advanced Essay Writing.” He had a PhD and could have earned tenure, but he was more into teaching and, in his free time, writing 3,000-plus recommendation letters for students as well as a massive (1,100-plus page) novel he worked on for more than three decades.

John’s manic energy, wit, life philosophy, and dedication to the success of his students as writers and human beings has made him an exceptionally influential figure in the lives of many of the roughly 4,000 students he taught at the University of Michigan, Purdue University, and Lincoln Memorial University since the mid-1970s. Based on student evaluations, he was among the highest-rated professors at Michigan for more than three decades.

Years before, I had proposed the idea of John and I collaborating on what we came to call “our dirty grammar book.” I naively wanted to capture his teachings – naive because you can’t capture John’s teachings be merely relaying the content of his lessons. John succeeded so resoundingly in large part because he created an environment of trust and openness in his classrooms that is a model to be followed, but one that takes a special kind of teacher to instantiate.

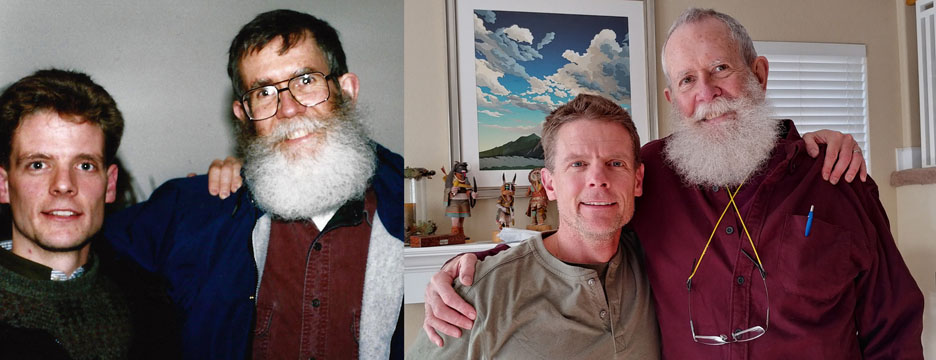

Regardless, now, suddenly, in what would have been the fall 2018 semester, John had time to collaborate. He flew out to Denver in late November that year to spend a week with my family and me.

We talked grammar, but we also did some field trips. We went to Breckenridge to visit former student Emily Higgins, to the home of his former student and Denver Broncos tight end Jake Butt, to the Butterfly Pavilion, to watch my daughters figure skate and play soccer, and elsewhere. We discussed his life.

John doesn’t think his life was interesting. He is wrong.

We talked about his firing, too, and I obtained of some interesting documents – documents that that would shed light on John’s firing. The timing was fortunate: he hadn’t yet signed the January 2019 nondisclosure agreement (NDAs) tied to his settlement with the University of Michigan. From then on, he has had to remain silent.

But I had what I needed.

These NDAs have made stories such as that of John’s firing (John would bristle at the fact that I just used “such as” and provided only one example; he prefers two or more after “such as,” “for example,” and “like”) very difficult to share publicly. That’s a problem. John’s firing demonstrates how #MeToo – a vital social movement tackling the scourge of sexual harassment – can be twisted into an excuse to fire the innocent. John surely wasn’t the only one. In his case, the innocent was a then-78-year-old who was impolitic, foul-mouthed, and a lover of dirty jokes – but no sexual harasser.

Still, the firing (he was subsequently given a settlement and retired – this I can tell you because I FOIAed the settlement agreement) is only part of the story. To me, the book is about, as John describes his own life, “a tragic life well-lived.”

He knew poverty from a childhood lorded over by an alcoholic father and an adulthood spent chasing life experience and intellectual gratification rather than money. He lost a young wife and two baby boys. He caught dogs in Wisconsin, raised pigs in Tennessee, sold insurance in Indiana, counseled soldiers in Germany, and, on a Fulbright, had his apartment bugged by the Romanian secret service.

Our lives are all unique; John’s is more unique. He never made much money. He never rose to lofty academic heights. He never sold a million books. But he met with, to borrow from a Henry David Thoreau quote, one of John’s favorites, “a success unexpected in common hours.”

I think John’s biographical story rolls nicely the investigative story in A Beard Cut Short because the combination of understanding John’s life and the great good he did for so many people drives home the true costs of #MeToo gone awry.

So that’s the book. It’s out now. I popped a few old photos up on a Facebook fan page. It’s a quick read, teaching and enlightening as it entertains – or that was, at least the idea.