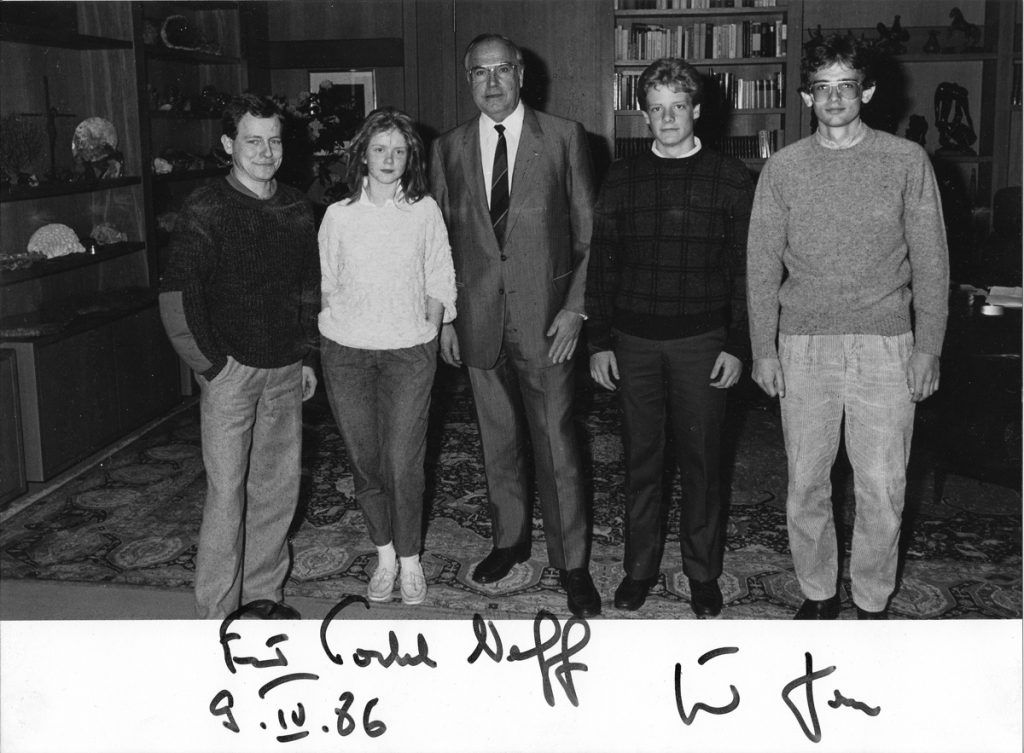

From left, Jochen Messemer, Caecilia Hanne, West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, Todd Neff, and Frederic Pflanz on April 9, 1986.

We had been scheduled for 15 minutes, but between Helmut Kohl’s meetings with economic advisors, discussions with coalition partners about what to do about the assumed bombing by Libya of a Berlin discotheque four days before – plus having to squeeze in a meeting with East German Politbüro member Günther Mittag – there was only time for a quick photo op.

It was April 9, 1986. My host brother Frederic and I had woken at 6 a.m. in the Ludwigshafen suburb of Oggersheim, West Germany, a bit earlier than for a normal Wednesday school day at Carl-Bosch Gymnasium. We were going a bit further than downtown LU, instead taking the train to Bonn, the capital, to meet Helmut Kohl, the country’s chancellor.

I had turned 17 a few months earlier; Frederic would turn 18 in a few days. I was an exchange student; he had been an exchange student the previous year. Both of us were part of the Congress-Bundestag Youth Exchange Program. It had launched a couple of years earlier. The program, jointly funded by the U.S. and West German governments, sent an American high school student to each Bundestag district in Germany and a German high school student to each U.S. Congressional district. The idea was to deepen U.S.-German ties in a Cold War era during which the threat of Soviet tanks rumbling through the Fulda Gap was quite real. Frederic, from Oggersheim, had spent a year in Kankakee, Illinois. I, from Dearborn, Michigan, was now in Oggersheim, the temporary third son of a family named Pflanz.

Oggersheim happened to be where Helmut Kohl was from. In the West German parliamentary system, the chancellor is also a member of the Bundestag. I had landed in Helmut Kohl’s district. And so, three-quarters of the way through my exchange year, Helmut Kohl’s staffers arranged for us to meet – actually, they had arranged for quite a bit more. This was an overnight trip, one that included a stop by the equivalent of the FBI headquarters in Wiesbaden, where we watched an anti-terror exercise, and also by the German Space Agency. All because, by random chance, I had ended up in the big guy’s district.

The moment crystallized in my memory is that of entering the enormous office and seeing the man at his desk, hurriedly checking something on a short stack of paper. He stood, confirming his famous size – six-foot-four, though at that point he was far short of the 300 pounds his obituaries last month cited. He wore a silvery suit that seemed to glow.

He shook all our hands, his grip soft, as if to offer comfort in the presence of such mass and gravitas. As we lined up for the photo we chit-chatted – he was surprised at my German: “Er spricht doch schon gut Deutsch.” I’d been immersed in a German family for nine months, so my German was in fact getting there, the fruits of countless hours of cramming and smile-nodding at things I scarcely understood. But Kohl’s infamous lack of foreign-language skills lent an irony to the comment that even a 17-year-old could grasp.

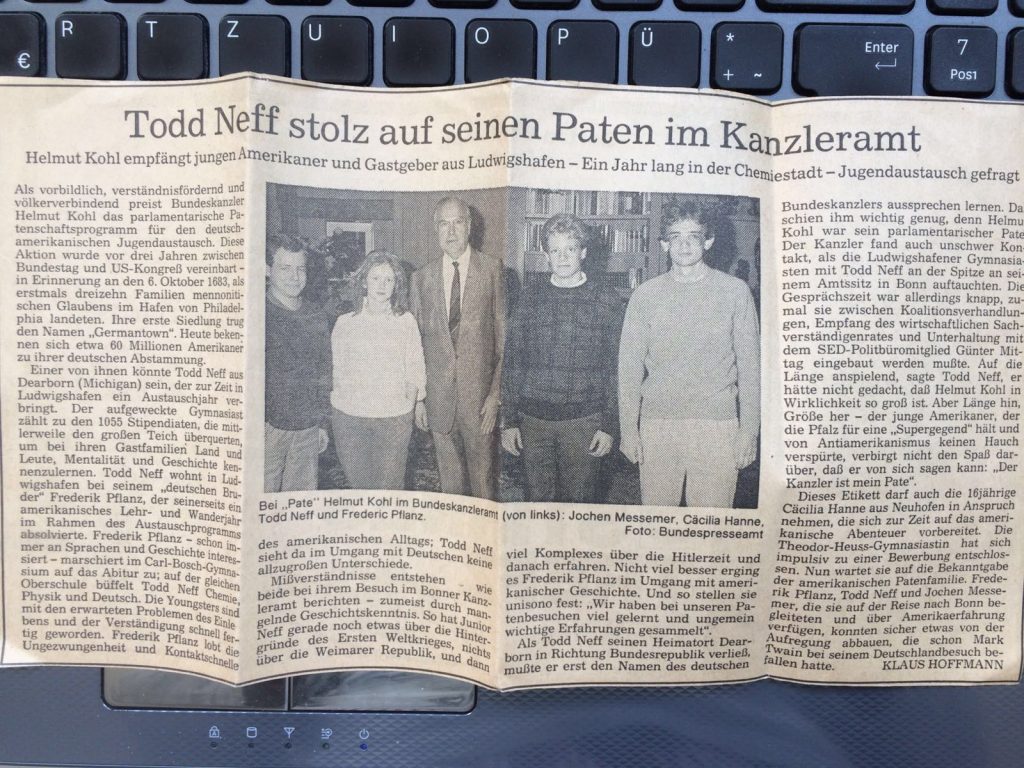

Within a minute or two we were hustled back out, to a conference room where an old reporter named Klaus Hoffman soon arrived. As a journalist now, I recognize this visit by teenagers as something between a very soft story and a nonstory. Hoffman was the equivalent of a White House reporter, though, and Die Rheinfalz was a big regional paper. Hoffman was a verygood writer, which I might have recognized at the time had I been able to read his product without consulting a dictionary. The headline: “Todd Neff Proud of His Godfather in the Chancellor’s Office.”

The real story would unfold much later, and it has to do with the Congress-Bundestag program itself. I can’t find the above article. A friend of mine WhatsApped it to me (notice the “Ü” on the keyboard above the headline, and the “€”, and the “Z” where the “Y” should be). That friend, Christian Volz, was a classmate of mine in 1985-1986. He and his family are visiting my family in Denver – tomorrow, in fact.

Last summer, his sister and her family visited, as did Frederic and his family. The summer before that, my family met that of Andreas Macha, another classmate, in San Diego. The summer before that, Andreas rented a big van and drove the two families around Southern Germany, and Christian hosted a “Welcome Neffs” party for about 50 folks. I’m a godfather myself now – to Frederic’s son Phileas. If you include the kids, there are several dozen people in Germany whom I count as close friends, and my kids are friends with their kids now, too.

This all has political implications. Particularly in our current environment, there are dozens of Germans who know that not all Americans agree with what’s being currently purveyed as public and foreign policy. They have a personal connection to the United States they wouldn’t otherwise have. The real story is that the Congress-Bundestag program, as relates to this kid from Dearborn, worked in ways neither its creators nor its participants could have imagined.