Items from the New Horizons launch press packet, which have been hanging out in a Southwest Research Institute folder for nine-and-a-half years.

You may have heard: NASA has a mission flying past Pluto tomorrow. New Horizons. The thing’s been in space for nine-and-a-half years. I was there at the launch, covering it for the Boulder Daily Camera. Wrote probably 15 stories about the mission, several of them from Cape Canaveral. It was my first and only live space shot. I can still feel the Atlas V in my gut if I sufficiently still myself.

It is my second-most-favorite-ever space mission, after Deep Impact, around which I based a book. I wanted to write a book about New Horizons, too. The focus would have been about its principal investigator, who is a big boss with a PhD. Alan Stern, based at the Southwest Research Institute offices he had founded in Boulder, a remarkable dude. We sat down for lunch maybe three years ago and talked it out. He was game. I pitched it as “Pluto Man,” though that’s a pretty narrow view of the actual man, in retrospect. Alan was very nearly an astronaut, served as NASA’s head of space science (this after the New Horizons launch) and has become a major player in NewSpace. That’s jargon for Blue Origins, SpaceX, Virgin Galactic and their ilk. So there’s much more going on with this man than just Pluto.

The pitch didn’t achieve orbit, you could say. I talked to Alan again and proposed a Kindle Single, maybe 30,000 words. That seemed to be going somewhere until it didn’t seem like it anymore. I wondered if, having found it difficult to find a market for a book about a lot of interesting people in the space business, it might be a similar challenge with Alan Stern and New Horizons. And then I sort of let it go, knowing that Alan and his team would be getting no shortage of attention as their craft approached Pluto. I do kind of regret it now.

But then, Michael Lemonick’s story in the June 2015 edition of Smithsonian, “One Man’s Lifelong Pursuit of Pluto is About to Get Real,” is along the lines of what I’d have put together, and tens of thousands of words shorter.

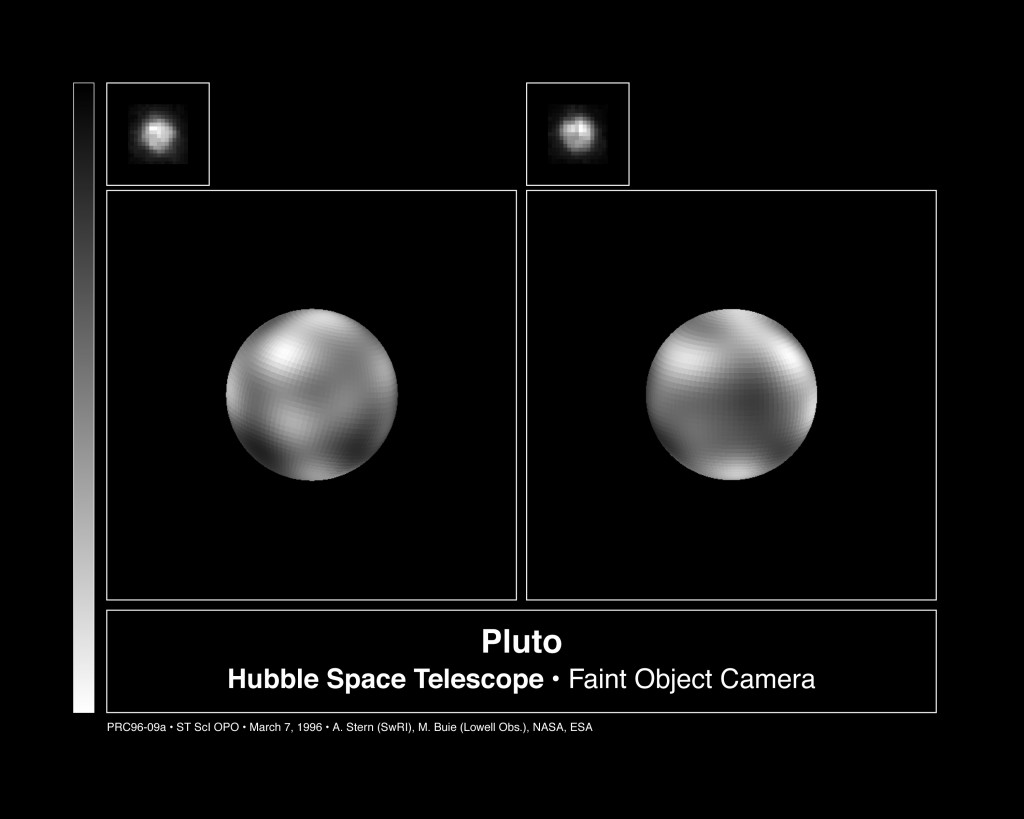

New Horizons is an amazingly cool thing, truly as exciting as any robotic space mission we’ve ever done. I mean, it’s traveled 3 billion miles over nearly a decade just to get to the point. We know so little about the place — when Ira Flatow asked Alan on the most recent Science Friday how much we don’t know about Pluto, he responded in the converse, saying we could fit what we do know on a couple of 3×5 cards. Given that Alan co-wrote a book about Pluto, this was more media savvy than statement of fact. But compared to any other of our solar system’s non-Oort bodies, the dwarf planets of the Kuiper Belt remain the least understood. And the photos already coming back — well, to put in perspective how much better they are than what we’ve had heretofore, check out this, which was, until New Horizons’ approach, the best we had ever mustered:

Hubble’s view of Pluto, taken in 1996. Note that Alan Stern and Mark Buie, both on the New Horizons team, were credited. So Stern will have been responsible, more or less, for every decent image we have of Pluto. Also note that the crisper, bigger renderings aren’t what Hubble saw; Hubble saw the blobs in the corners up top.

I’m going to stop now, before I start repeating a bunch of stuff Emily Lakdawalla has already said far more professionally.

I kept my media kit back in 2006, from which I’ve scattered photos about this post. To add length to accommodate them all, I’ll add my favorite of my New Horizons stories, mainly because of the lede. I loved that this brilliant, successful space scientist on the eve of his second-greatest career moment (his greatest happening tomorrow, upon New Horizons’ flyby) was wearing a ring his dad had bent and welded into shape from a NASA lapel pin.

Space exploration project was a long shot

Daily Camera, The (Boulder, CO) – Friday, January 20, 2006

Author/Byline: Todd Neff Camera Staff Writer

Section: News

Page: A01

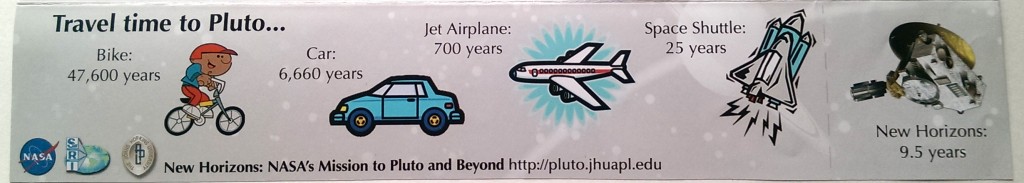

Part of the New Horizons education and public outreach offerings included a growth chart. My kids didn’t hit the bottom of the chart at the time, being 3 months old and two-and-a-half years old at the time. They’re nearly 10 and 12 now.

In the days leading to Thursday’s successful launch of the New Horizons mission to Pluto, Southwest Research Institute scientist Alan Stern wore a bulky ring crafted from a NASA lapel pin, a 10-cent piece and a steel bolt stretched and shaped to hug his finger.

His father, Leonard, 74, made it for him.

“It’s kind of hokey, but I wore it for good luck,” said Stern, the Southwest Research Institute scientist from Boulder leading the largest scientist-led mission in NASA’s history.

It took more than luck to bring New Horizons to the launch pad.

“I never thought it would get here,” said Ed Weiler, the NASA official who approved New Horizons on Nov. 29, 2001. “New Horizons was a mission with a history of meeting impossible requirements repeatedly.”

Weiler is now head of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., which did environmental testing on the spacecraft.

For more than a decade, at least three Pluto missions – Pluto 350, Pluto Fast Flyby and Pluto Express – had gone nowhere. Weiler pulled the plug on the Jet Propulsion Laboratory-led Pluto Express in September 2000. Its projected costs had ballooned from about $500 million to roughly $1 billion.

Three months later, Colleen Hartman, then NASA’s Solar System Exploration Division director, concluded that a Pluto mission had to happen by early 2006. As of Feb. 3, Jupiter’s orbit would no longer provide a gravity assist, delaying Pluto arrival by as much as five years.

In addition, Pluto reached its closest point to the sun in 1989 and already was receding on its 248-year orbit. Each passing year increased the risk of Pluto’s atmosphere freezing and collapsing into a nitrogen frost that snows onto the planet’s surface. That would pare back substantially a Pluto mission’s scientific bounty, and the planet wouldn’t warm again for more than 200 years.

Weiler agreed, and Hartman’s group released a detailed call for Pluto mission proposals within a month; that step typically takes six months. The spacecraft would require a suite of miniaturized, energy-efficient instruments with few, if any, moving parts. It would need to be prepared for the chilly rigors of the solar system`s outer reaches. It also would need a nuclear power source and a major-league rocket.

The craft’s nuclear power source – needed for missions venturing too far from the sun for solar panels to work – presented another challenge.

As many as 40 federal, state and local agencies had to sign off in record time. Hartman, now a top official in NASA’s science mission directorate, credits long hours at NASA, the U.S. Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency, the White House and elsewhere.

“When we approved (New Horizons), we knew that a lot of people would pull for a mission to this blessed little planet, and that they wanted to make it happen,” she said.

Stern would agree. At the post-launch news conference Thursday, he thanked the thousands of people who contributed to the effort in various ways.

But Stern’s leadership was vital. Glen Fountain, the New Horizons program manager at Johns Hopkins University`s Applied Physics Laboratory, which built New Horizons, said Stern had a vision of where the project needed to go and what had to get done.

Fountain alluded to Stern’s habit of giving team members pencils sharpened down to a stub.

“This little pencil is about persistence – that`s the key. You do not stop. You keep going,” Fountain said. “Alan had that vision for years. He brought that vision to the team.”

As for what his vision was, Stern closed with it in his 1998 book, “Pluto and Charon.”

“To see the solar system’s ninth sister as she really is, we must go to her. And amazingly, our species has developed the will, and the way, to do just that,” Stern wrote. “So guard your secrets while you can, Pluto! We are coming.”