Mashable published my story on what is probably going to be the future of drug testing today. I figured I’d add a bit of backstory.

Mashable published my story on what is probably going to be the future of drug testing today. I figured I’d add a bit of backstory.

I came across CU Toxicology and their high performance liquid chromatography/dual mass spectrometry (HPLC/MS-MS) drug test while doing a story for University of Colorado Hospital’s biweeky online magazine. It struck me as something that had a lot of interesting ingredients for a bigger piece for a wider audience. Then I thought of Mashable. I’d worked with Josh Catone, the site’s executive director for editorial projects, in the summer 2013. He had come across a story I’d done for Smithsonian Air & Space and was looking for a Colorado writer to do a piece on ET3 with a Hyperloop hook. I liked working with him and his colleagues. So I pitched him. Here’s the pitch, as they say in baseball. I sent it off on January 6:

From the state that just legalized recreational marijuana comes a new drug test so sensitive and broad-based it can sniff out about anything you’ve been toking, smoking, sniffing, shooting or popping.

The urine test, which relies on parallel mass spectrometry and proprietary algorithms, was developed by a nonprofit based at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. It’s led by a former Silicon Valley venture capitalist named Blair Whitaker and a small group of CU anesthesiologists.

CU Toxicology is poised to pull drug testing technology out of the 1970s, where it’s been mired, and provide an alternative to expensive, narrow drug tests offered by major labs. The test also shows promise in changing outdated approaches in areas as diverse as pain management to geriatric care (for, say, seniors who forget what meds and how much they’re on). The test has the hallmarks of a potent new tool with still-unknown applications. From the perspective of those of us being tested, it looks like an NSA program for our bloodstreams. And while CU Toxicology is pioneering this full-spectrum approach to drug testing, others using similar hardware are sure to catch up.

Conventional drug tests look for a few of the usual suspects (THC, cocaine metabolites and so forth) using something closely related to a pregnancy test. The CU Toxicology test, in contrast, pushes modern mass spectrometers to the limit, cranking out parallel data on 112 compounds in 16 classes (anticonvulsants, antidepressants, benzoids, cannabinoids, opiates and so on). These compounds are the active ingredients in about 500 drugs. All of it happens in a few minutes.

In addition to providing a broad snapshot of what someone’s taking, the test is far more sensitive than traditional approaches. A standard screen for codeine cuts off at 300 nanograms per milliliter; CU Toxicology’s detects down to 10 ng/ml. For THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, the standard screen cuts off at about 50 ng/ml; the CU test sniffs out 2.5 ng/ml. It can tell if you’ve been trying to detox, too.

CU Toxicology’s origins story is interesting in that Whitaker learned about the nascent product from his anesthesiologist neighbor. An animated, MIT-educated software and telecommunications expert, Whitaker recognized that the chemistry was only part of the solution. They needed software to make sense of the data pouring out of the machines. With CU Toxicology’s test in quiet commercial use for about 18 months now, Whitaker is now confident enough in the technology to take it public. Whitaker, who handles everything from marketing to mailroom duties at the moment, aims to grow the lab into a monster nonprofit lab-services giant in the mold of Mayo Medical Laboratories.

The Denver Business Journal and Colorado Public Radio are the only media I’m aware of having picked this up. The University of Colorado press office did a feature on it last summer. I think it would be of national interest, in particular among those who worry about drug tests, and a good fit as a Mashable Spotlight, for which I did a piece on Daryl Oster last summer.

Cheers,

Todd

Josh was enthusiastic and said this felt like more than 3,000 words; I said, no, c’mon, Josh, I can get it done in 3,000. So we settled on that number. I filed 5,250 six weeks later.

What the hell happened?

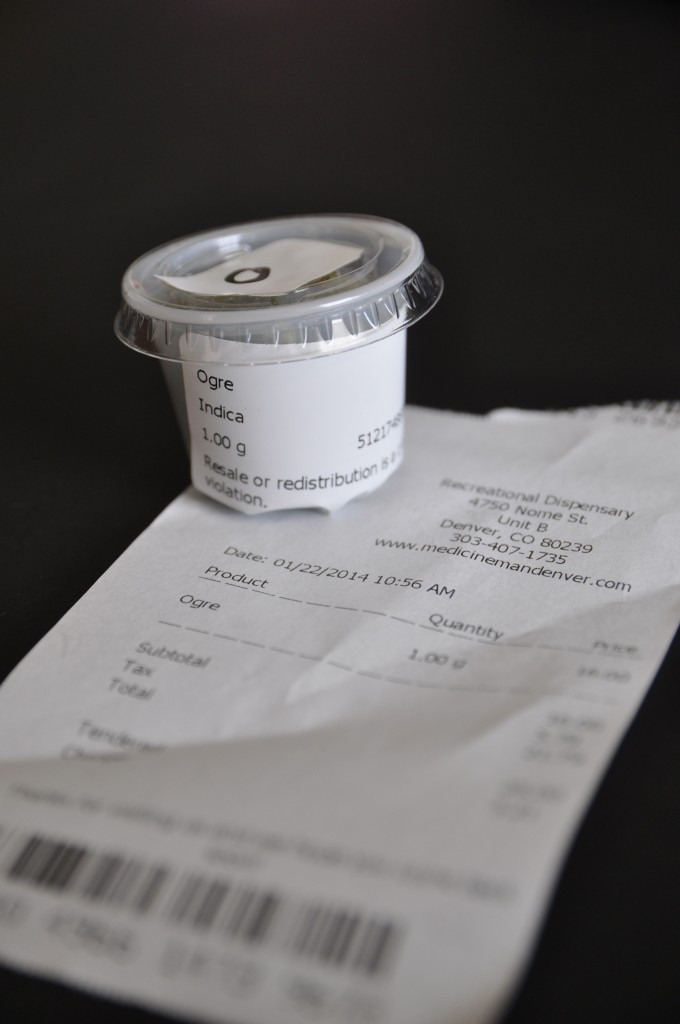

Well, it dawned on me (in the shower, cliche, I know) that the best way to tie together the yin-yang of Colorado as a) home to legal recreational marijuana and b) Colorado as home to a crazy-accurate and wide-ranging drug test was to have me buy the the stuff somewhere (where, I didn’t know — the Denver Post’s “The Cannabist” section helped there), smoking it, and getting tested. Going gonzo, basically.

I bounced this off Josh first; he gave the green light, with the caveat that expensing the weed would be dicey. Then I bounced it off CU Toxicology founder Blair Whitaker, who was enthusiastic. I proposed paying for a single test (Mashable was amenable to paying for the maybe $200 that might cost); Blair said doing a few tests over a few days and watching the THC levels drop off would be more useful to him. I figured that would be more interesting to write about, too. He could add a few samples to a mass-spec batch and chalk it up to R&D he said. No charge.

I considered whether accepting $1,600 in retail-value urine drug testing represented a breach of journalistic integrity, but concluded that the service was of no value to me outside the bounds of the story. He dropped off a bunch of cups and a sheet to fill out with dates and times a couple of days later.

I assumed, of course, that the CU Toxicology test would spot THC in my system despite the pee-cup at Wiz-Quiz showing a negative. If you made it to the end of the story, you know it didn’t turn out quite that way.

Which was why it turned out to be so important to have my friend Louis’s sample handy. He happened to be in town and happened to have rheumatoid arthritis and be on a lot of drugs to help with the pain. I knew he would want to smoke, something I do maybe quarterly, if. I asked if he’d play along, assuming that he’d light the CU Tox test up, which he did.

In many ways, the piece played out as most stories do: what you think you’ll be writing about isn’t exactly what you end up writing about. Reporting takes you unexpected places, and going with the flow yields better results than sticking slavishly to the plan.

My being THC-negative on the CU Toxicology super-sensitive test despite the pee-cup positive meant a bit more reporting. I asked Blair what he thought might have happened. I talked to Heather Despres over at CannLabs. The gist of the story didn’t change — that these broad, sensitive drug tests are coming, that they can be good and bad, and that we need to be ready for both. But the THC surprise opened the door to a brief but important discussion on the stupidity of marijuana being a schedule I drug in the eyes of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, if only because it makes it harder for scientists to understand what it’s doing in — and to — our bodies.